Silent killers of the immune system

- Morgan Greenewood

- Jun 9, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Oct 1, 2025

Writer: Morgan Greenewood

Editors: Allie White, Sam Alper, and Sarah Brockway

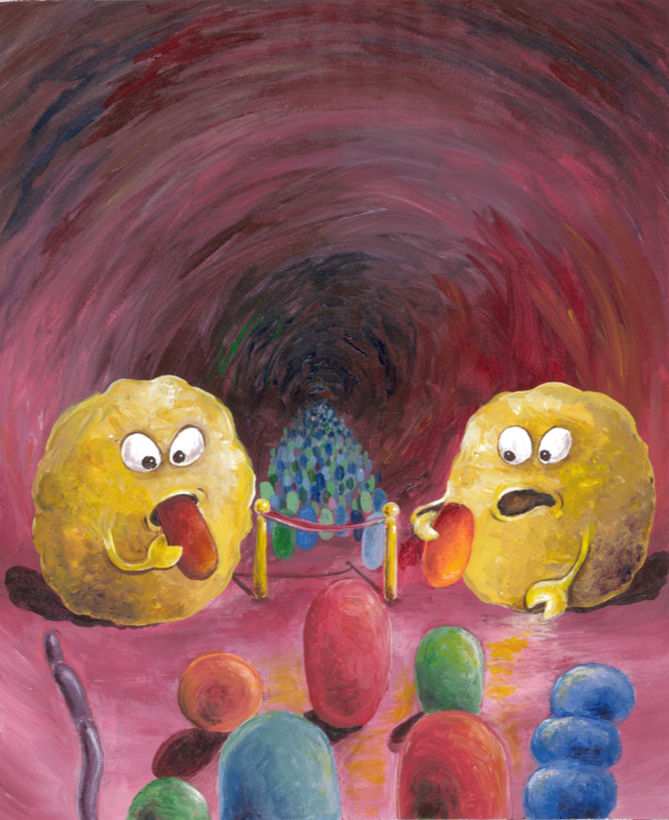

Illustrator: Darci Ott

Within each of us lives a vast, bustling community of trillions of microscopic organisms. This diverse collection of bacteria, fungi, and viruses is known as the microbiota. In recent decades, scientists have come to appreciate just how essential this community is – not only for our overall health but also in shaping the onset and severity of many diseases.

Our journey with these microbes begins at birth, as we are colonized by the microorganisms living in the birth canal, skin, and environment around us. These organisms create an ecosystem on and in many parts of our body, including our skin, mouth, lungs, and, most abundantly, our intestines. This ecosystem resembles a community where each microbe has a role. These roles can range from breaking down complex carbohydrates, taking up space to prevent other potentially bad microbes from invading, and even educating our immune system on how to combat infections. As we grow older, many factors, including our diet, lifestyle, and even exposure to antibiotics, influence the development of this microbial community. It is truly a lifelong relationship, and for the most part, it is a good one.

In fact, having microbes in our body is not just something we have adapted to: it is something we depend on. For example, mice that lack a microbiota – known as germ-free mice – have a compromised immune system, including a reduction in immune cell numbers, leading to a reduced ability to combat infections and other diseases. Indeed, we know that these tiny organisms play a vital role in shaping our immune system by educating it to recognize and respond to dangerous microbial threats. However, not all microbes are clearly good or bad. In fact, many beneficial microbes closely resemble harmful ones.

This is where our immune system comes into play. Like a well-trained security force, our immune system consists of immune cells that constantly monitor the body for invaders, identify threats, and launch attacks as needed, keeping you safe. But the immune system has a particularly tricky job when it comes to the microbiota. It must strike a delicate balance in defending against dangerous microbes while also tolerating and even supporting the helpful ones.

So, how exactly does our immune system decide which microbes to keep around and which to eliminate?

To navigate this dilemma, our immune system uses a variety of surveillance mechanisms to monitor the microbial landscape. These sensors are designed to probe the microbiota and identify any potentially harmful microbes. Upon identification of microbial threats, these patrolling immune cells will sound the immune alarm, which works well for most parts of the body. But in microbiota-rich areas like the gut, where microbes are abundant, constantly triggering immune responses would create chaos. Imagine if your smoke alarm went off every time you lit a candle; it would be disruptive, to say the least.

Fortunately, life has a more elegant solution.

Recent research from Dr. June Round’s laboratory at the University of Utah has uncovered our immune system’s solution to this dilemma: an immune sensor that keeps the microbial balance in check. This sensor, called Clec12a, is a protein on the surface of immune cells. It can be thought of as a set of binoculars used by immune cells to keep a watchful eye over our microbial community without causing unnecessary immune activation.

What makes Clec12a unique is its stealth. Unlike other immune surveillance mechanisms that sound the immune alarm, Clec12a does the opposite. When it detects potentially harmful microbes, it acts quietly. This immune sensor selectively eliminates the threat by uptaking the harmful microbe into the immune cell, where it can be killed without activating the immune system. Since Clec12a avoids immune activation this allows for protection against microbial invaders while avoiding collateral damage to the healthy microbes nearby.

This “silent killing” mechanism helps maintain peace in the gut, allowing beneficial microbes to thrive while keeping harmful ones in check. It is a sophisticated and subtle system whose further understanding and manipulation may hold the key to treating diseases in which this delicate microbial balance is lost.

One such condition is Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). In IBD, the immune system is often improperly activated. While we normally think of the immune system as our protector, if inappropriately activated, it can damage the healthy microbiota and surrounding intestinal tissue, destroying the intestinal ecosystem. Dr. Round’s research group found that in experimental models, when Clec12a is absent or not functioning properly, the microbial balance is disrupted. This disruption leads to worsened colitis or inflammation of the colon, which is a form of IBD. This appears to be the case in humans as well. For instance, people who are genetically predisposed to develop IBD often have lower levels of Clec12a. Thus, this silent killer may play a crucial role in maintaining a healthy gut environment.

Currently, treatment options for IBD are limited and often involve broad immunosuppression, which can compromise the patient’s ability to fight off infection and other diseases. Discovering mechanisms that regulate our immune system in the intestine, like Clec12a, give these patients hope. If scientists could find a way to restore or enhance Clec12a function, empowering the immune system to selectively target harmful microbes without damaging the beneficial ones, they may be able to find a way to cure this awful disease. In other words, we may one day be able to give the immune system back its binoculars, helping to protect the body without unintentional damage. Truly, a promising vision for the future and a powerful reminder of the quiet complexity that lies within us.

Comments