The other white water: cocaine and other narcotic pollutants in ocean ecosystems

- Phillip Comeaux

- Jun 3, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Oct 1, 2025

Writer: Phillip Comeaux

Editors: Allie White, Sarah Brockway, and Sam Alper

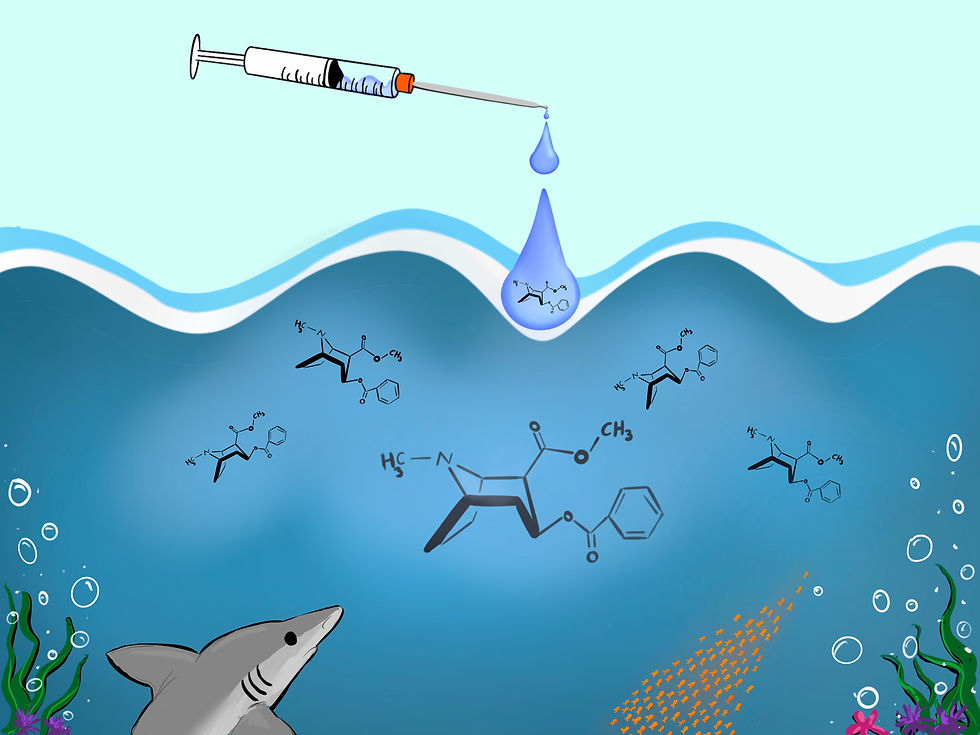

Illustrator: Becca Mellema

Tales of animals ingesting cocaine have circulated the internet for years. The tale of a black bear eating several kilograms of the drug was a particularly common one, and in 2023, a film inspired by the events was released to theaters. Cocaine Bear was a box office success, and so it joined the obscure genre of films titled after cocaine and animals. Later in 2023, filmmaker Mark Polonia released a horror film by the name Cocaine Shark to join the bears in this auspicious club. However, the film itself disappointingly contains no cocaine-addled sharks. This exercise in false branding is because the film is fictious; it is not a documentary. In our real world, evidence of narcotic drugs, including cocaine, entering the aqueous environment and the bloodstreams of the oceans’ top predator has been found.

Senior researchers at Brazil’s Instituto Oswaldo Cruz Enrico Mendes Saggioro and Rachel Ann Hauser-Davis led a team of scientists focused on public and environmental health to test the state of pollution in aquatic ecosystems, finding traces of cocaine and related chemicals in the organs of sharks captured in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Rio de Janeiro from 2021 to 2023. This finding is only the most recent report of drug contamination of water ecosystems, demonstrating the need to preserve natural ecosystems from unexpected dangers.

While the idea of sharks enjoying cocaine like the Sea Wolves of Wall Street may be an interesting visual, the health of the aquatic ecosystems of the world could be endangered by drug contamination. All sharks analyzed by the researchers tested positive for cocaine and by-products at levels significantly higher than results previously found in freshwater fish lower in the food chain as recently as 2016 in Argentina. This indicates a significant and potentially growing risk to the ecosystem, as well as endangering human health through fishing for food. Sharks were chosen as a sort of proverbial canary in the coal mine for the ocean ecosystem, since predators can see toxins accumulate in their systems. As sharks consume contaminated prey, toxins such as cocaine accumulate in their bodies. This is a phenomena called biomagnification which refers to the accumulation of toxins at higher levels in the food chain, a potential danger that is also posed to humans. A familiar effect of biomagnification in seafood can be observed with mercury, which warrants a warning for the consumption of large amounts of predatory fish, like tuna or swordfish. Similar to mercury, the presence of cocaine in the ocean food chain can make its way to humans. The shark studied by Saggioro, Hauser-Davis, et al was the Brazilian Sharpnose shark, a species that is fished and eaten by people in Brazil.

As suggested by biomagnification, sharks are not the only sea life to have been found with contaminant drugs in their systems. Other researchers testing contaminant levels in mussels, filter feeders at the bottom of the food chain, have found cocaine, other narcotics, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and more in other Brazilian waters, as well as those close to the UK and the US. But cocaine is not the only chemical in the water getting the seas high. Czech researchers testing a pond affected with treated wastewater feeding into a river found 18 different pharmaceutical drugs across the water, sediment, and fish samples. Of these drugs, most notably, the researchers found traces of methamphetamine, another commonly used narcotic drug. A follow-up study from another team of Czech researchers found that the level of meth found in the water would be sufficient to cause symptoms of addiction in trout.

The worldwide prevalence of pollutants in bodies of water could cause systemic issues to those environments. Changes to the environment, including those brought about by cocaine concentrations in water, have been shown to affect fish embryonic development. The Brazilian researchers who found the cocaine sharks cite several potential actions that can be taken to preserve delicate ecosystems, for the good of the environment as well as humans consuming affected sea creatures. Since the problem is global and prevalent, they suggest continuous monitoring programs to track contamination levels, as well as pollutant sources, to determine the routes by which water is affected. In parallel, they suggest additional studies into the effects of cocaine, methamphetamine, and other pharmaceutical contaminants on wildlife, in short-term and long-term timeframes. Lastly, they cite wastewater treatment unable to remove drugs from treated water as a failure requiring upgrade. While waste will always be a necessary by-product of human development, the findings in fresh and saltwater ecosystems indicate that there is not enough being done to ensure that the water we are putting back into the world is safe.

The recent discoveries of marine life with traces of narcotics in their systems show some unexpected ways that human activity can affect the environment around us. Water across the globe is affected by human waste as pollutants root themselves in the organs of the wildlife throughout the food chain. Whether it is European fish swimming in meth, American bivalves filtering in pesticides, or tropical sharks playing in the snow, human waste is a sickly toxin endangering everything it touches. Because unlike a B-tier science fiction horror film, the real world does have cocaine sharks, and it is possible we have not fully seen the horror that can bring.

Comments